An exhibition of a little known, but enchanting culture is on view at the Institute du Monde Arabe in Paris: “Sur les Routes de Samarcande, Merveilles de Soie et d’Or”. Over 300 pieces of embroidery, carpets, jewelry are brought over from Uzbekistan, a Central Asian state that used to be one of the republics of the Soviet Union.

Uzbekistan is the heir of several ancient kingdoms, such as Khoresm and Bukhara. Samarkand, the city of blue and green Mosques and Madrases, is mentioned in the exhibition title as a place that might be more familiar for a Western traveler, but the exhibits represent many different regions of Uzbekistan, including the fertile Ferghana Valley and the present-day capital, Tashkent.

The exhibitions opens with what one could consider a pièce de résistance, the emir of Bukhara ceremonial robes and headgear, glistening with gold embroidery of unbelievable intricacy and beauty. Only, then more and more such robes come into view, all different in ornament and the underlaying tone of brilliant blue, green, black silk. The Emir Muzaffar-Ed-Din, who ruled Bukhara from 1860 to 1885, loved the gold embroidery, and gathered in his palace workshops dozens of best embroiderers. Men’s robe, or mantel, called Chapan, could be completely cowered with embroidery, or could be made of expensive velvet, imported from China, Persia, of even Europe. In such cases, embroidery adorns the edges of a garment and forms a large medallion on the back.

A chapan is complemented by various undergarments, a belt, also richly embroidered with golden thread, similarly decorated boots, and ceremonial arms.

Heavy men’s chapan worked as thermal insulation, protecting both from cold in winter and excessive heat, to over 50* in summer. Women of the ruling class spent most of their time indoor or in the palace gardens, so they normally wore lighter layered clothes, made of silk and cotton. The dress code dictated that girls and young women would dress red, women over thirty would wear green or blue, while older women would wear pale colors, such as beige. But these were just the predominant tones, and a dress could include other complementing colors, brought by embroidery or through the use of the Ikat – traditional fabric woven with thread dyed in different colors.

An important part of the feminine world was played by the Suzanis. These large pieces of embroidered fabric were a part of a girl’s dowry. Unlike the gold embroidery, executed by skilled artisans for powerful and rich clients, Suzanis were created by girls themselves. Using a Suzani as a wall hanging or a bedstead, a young woman always had with her a remainder of her parents’ home, were she had worked on it, sometimes for several years.

There are two main typologies in the ornamentation of the Suzanis. One, with colorful floral motifs, alludes to the Garden of Eden. Another, with bold solar and astral shapes, symbolizes the celestial Paradise. Both were meant to protect a woman, bringing her abundance, prosperity, security and fertility.

Floral Suzanis were created in the areal of Bukhara, and geometric ones in the areas culturally dominated by Samarkand.

The carpet weaving is an ancient art in Central Asia, and reflect traditions of many generations. Wealthy city dwellers could afford short or long pile knotted carpets, and nomadic peoples created and used mostly flat-woven rugs, that could be easily folded and transported, or felt mats. The particular motifs belonged to specific ethnic groups or clans, but all shared general protective symbolism.

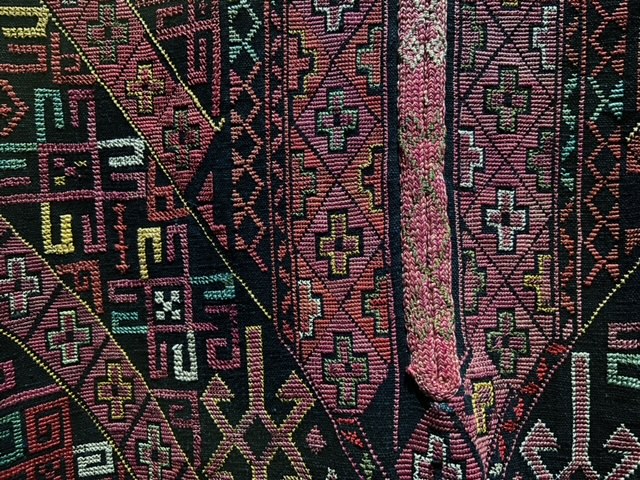

The multiethnic nature of the region is not easily perceived through the exhibition structure, but one ethnic group, the Karakalpaks, who lived near the Aral Sea, is presented in its own section. Karakalpak women’s clothes are clearly distinctive: geometric patterns of cross-stitch embroidery cover the front of the dress, dissolving to the side panels. The combination of symbols and colors showed the status of a woman and her affiliation with one or the other clan and family.

The final installation of the exhibition presents clothes made from the Ikat. Brilliantly bright and at the same time wonderfully harmonious male and female robes from different areas of Uzbekistan are seemingly floating on air, enchanting even the most skeptical visitors.

Possibilities to see something that impressive and inspiring do not come that often, so this exhibition at the Institute du Monde Arabe definitely worth a visit.

The exhibition “Sur les Routes de Samarcande, Merveilles de Soie et d’Or” was organized by the Institut du Monde Arabe with the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation.

Comissioners: Yaffa Assouline, Élodie Bouffard, Philippe Castro and Iman Moinzadeh. The authors of the exposition Les ateliers de l’Ouzbékistan.

Written by: Anna Bronovitskaya