Art decision offers an interpretation of Kazimir Malevich’s paintings from art expert Irina Vakar:

Irina Vernichenko:

I have spoken to Irina Vakar; an art historian, writer, curator, and senior researcher amidst the crowded exhibition halls of the New Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

– The curators of the “Rouge” exhibition at Grand Palais, Paris (May- July 2019) have chosen the late art of Kazimir Malevich. Please tell artdecision’s readers about Malevich’s late paintings and his turn to figurative art in the end of the 1920s.

Irina Vakar: “It is remarkable that recently, about 20-30 years ago, when we started researching Malevich, the art of his late years was not seen as having value. It was considered that he betrayed the innovation, the “non-objective art », abstraction and the artistic progress when he had moved from “Suprematism” to figurative art. Now this is viewed in a different way.

After Suprematism [of the early period], Malevich was silent as a painter and delved into theory, philosophy, and innovative ideas about the reform of artistic education, all of which did not concern his artistic practice.

He travelled to Germany in 1927, and he might have noticed that a global U-turn occurred at that time there: the public, the critics lost interest in abstraction and the painters turned to figurative painting – in a new way. He too seemed to have started thinking about it (while still popularising “Suprematism” in Germany).

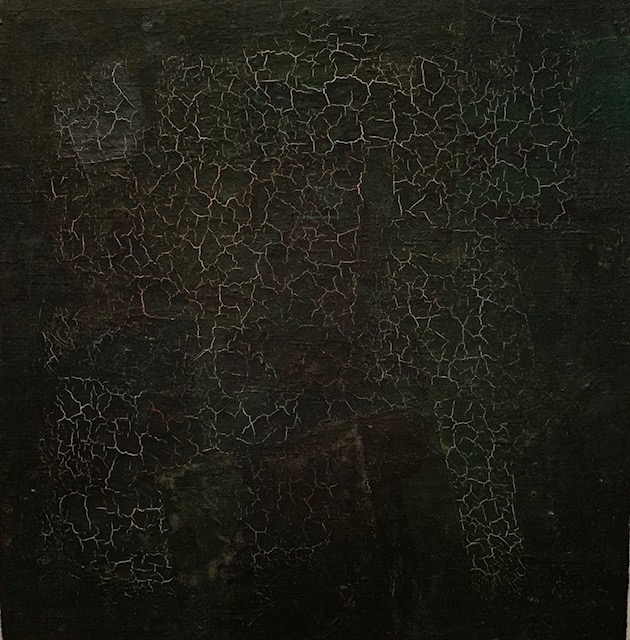

An opportunity came by; he turned 50 and wanted to do a personal exhibition in the Tretyakov Gallery, where he had friends, however this came during an absolutely inappropriate political moment. In 1929 Stalin declared a “great turning point”, the launch of “collectivization”, and the start of an ideologically terrible pressure; an attack on the Left, especially on the “Formalists”. Nevertheless, the exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery was arranged in December 1929. Malevich encountered the following difficulty: he did not have any more paintings left as he had left them in Germany, so he began painting new ones, and thus experienced a boom of creativity.

EXHIBITION OF 1929

There are different plots: why did he restore old works and why would he date them earlier than their actual year? At the end of the 1970s art historians realised that those dates [on canvases from exhibition of 1929] were wrong, that “Impressionism” was not painted in 1904 as he marked on the canvas, but in 1928-29, that “the peasants without faces” were not of 1912-13, but late 1920s. This body of artwork enthralled us, we understood it was outstanding, beautiful, but it was shown as “appendages” to “Suprematism” at the exhibitions in 1980s.

Malevich’s personal exhibitions started in 1978, the year of his then deemed 100th anniversary (he was born in 1879 though). In Dresden, in the Pompidou Center the late paintings were shown with the artist’s, “wrong” dates. But already in 1988-1989 there were Malevich’s large-scale exhibition in Russia and in Amsterdam. I participated in the preparations, and in the exhibition’s catalogue two dates were mentioned in connection with these paintings, e. g. 1913 and 1928.

Finally, all the experts arrived at the conclusion that these [paintings from exhibition of 1929] were his late works and our task was to freshly re-evaluate them; our eyes opened, and we realized that these were oeuvres of very high quality. First, Malevich was creating them armed fully with skill, as he had come a long way in art. He had been teaching and he followed the creative work of young artists, his students. Second, they contained a lot of new meaning.

By the way, the first one who discovered that was an American researcher, Charlotte Douglas. She realized there was a new worldview and that it was linked with his return to tradition.

In the early years (when Malevich was discovering “Suprematism”) he was saying that one has to abandon “the horizon ring”, when an artist always introduces coordinate system: the notions of “up”, “down”, “earth”, “sky”- and thus, expresses the same worldview as the artists of the Renaissance. However aviation has already invented space without horizon and discovered flight, and the artists can not think as before. 1915-1916 saw his angry manifestos destroying all figurative art based on classical standards.

But a turn happens [in 1929] , and a very important element returns, namely the horizon, the sky, the earth and a man in the center.

TURNING- POINT

Why? Largely because of the activism of the generation that was feeling the revolution not as a political and a social one, but as the air they were breathing; they permanently sought changes, as in the song: “Changes, we want changes”, (“Peremen, mi jdem peremen”), when it was impossible to live as before. It was impossible to listen to that criticism, to listen to that audience, and you have to zoom away from all of that.

In 1926 when the Ginhuk Institute where Kazimir Malevich has been teaching was shut down, he travelled to Germany. He wanted to stay in the West, however, he didn’t as a result of not knowing the languages, as well as feeling of being not really in demand. Art had progressed, Mondrian had invented “Neoplasticism”, “prouns” of Lissitzky were seen as a new word. Malevich, the inventor of Abstraction, was respected but not useful at that moment; he was not a constructivist, he didn’t like making things – he was a philosopher. Here he experienced a turning point.

His worldview changed. The sky and the earth return, and with it the values returned, the human returns to the centre, as there is no human, no portrait, no human face, no nature in the “Non- objective art”. The figure of this human is not abstract, it has certain features: it is a peasant, a Russian peasant man or a woman, in a long dress, with a covered head, a generalized figure, without facial features.

He did not abandon Suprematism, he called it “Suprematism in the contour”. The figure is structured simply as a sign, a sign of human existence, existence among the sky and earth, as a certain hierarchy of values. He linked peasantry with Christianity, and derived the Russian word for “peasantry” – “krestjanstvo” from the word for the “cross” – “krest”: krest\ krestjanstvo.

CONSERVATIVE UTOPIA

It is surprising that this last peasant cycle coincides with “collectivization”, a tragic page in the history of Russian peasantry. I believe that he comes up here with a “conservative utopia”, utopia always appears as an alternative to the present. These paintings are the embodiment of some kind of human harmony. Many consider these paintings as tragic, but they are also very enlightened as the “Suprematic” universe has now returned to the earth, and the human is, too, immersed into it.

The new worldview is based on Christianity, but of a very specific kind. Earlier he rejected this concept of the world, but in 1920 he published a book “God is Not Cast Down”, where he accepts the idea of God.

What is Malevich’s main idea? This philosophy is wonderful in its own way: there are three ways to God. God equals perfection. Everyone seeks perfection, and perfection is quiet, when there is nothing more to strive for. For him it represented peace, we might say “nirvana”, but he didn’t say that as he was not familiar with Buddhism. In fact, it is Nirvana. For Malevich, the first path to achieve perfection is the route taken by modern civilizations: technology. However, perfection is unattainable, as there are always newer inventions. The second route is through the church, where one seeks peace.

The most important route, where there is no obsolescence of inventions, is art, both classical and modern, as it always holds value. Malevich said that: “it is not the life which should be the content of art, but art that should be the content of life, only in this way life will be beautiful”. It is utopian: that art is above all.

ARTIST-PROTEUS

Irina:“What about our time, is it in tune with the works of Malevich of the later period? You mentioned “Changes, we want changes”, “Peremen, mi jdem peremen” in connection with Suprematism, that is a quote from the song of the end of the 1980s. Or is Suprematism closer? It is not by chance that there were only paintings of his later period at the exhibition?”

I.V. :Better ask our public, especially the youth. Doing research on this artist, I am living more in that time rather than now.

Irina: Does Suprematism resonate more with you then?

I.V. :Not really, I love Malevich as a very creative person. Avant-garde is the work of people who themselves always want to change. Malevich had different periods and they are all very interesting, and not only Malevich; Goncharova, Larionov, Tatlin as well. Let’s take someone from the greatest artists: Van Gogh. He painted “Potato Eaters” in his early years in the Netherlands, then he came to Paris and began painting like the Impressionists. Then, he finally found himself, created many masterpieces, and we know mature Van Gogh of this period. And similarly, most of the world’s artists developed in the same way, maybe with the exception of Picasso.

Picasso has multiple faces. Picasso was even referred to as “Proteus-artist.” I later conclude from this (see my articles on Russian avant-guard) that the main quality of avant-guard artists is “proteism“, changeability. Take Tatlin, you will enter the exhibition halls of the New Tretyakov Gallery and see many of his paintings: “Naked” – a painting of incredible strength; “Counter-reliefs”, “Tower”, then his later lighter and airy paintings. You will understand that this artist was never immature (his immaturity was left behind) and never had a period of decline, he was just making discoveries, one after the other, and they were all different. Malevich was the same.

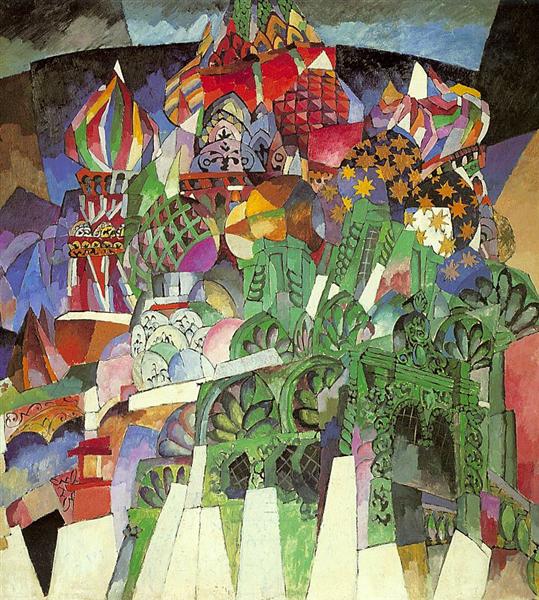

Malevich has tremendously powerful “Cubist” paintings; brilliant “Suprematism”, e.g. in the Tate museum. And he has incredibly amazing late works, for example, “White Horse” that was on display at the “Rouge” exhibition in Paris.

This is an absolutely symbolic, geometrized figure, a sign. At the same time there exists anxiety inherent in his later works of 1930-31, it manifests in its instability, in its worry, in this juxtaposition of bright colors in these slightly irregular, shifted proportions. These paintings seem to be very nicely built, constructive, geometrized, and at the same time otherworldly, and there is tragedy in otherworldliness. The city advances onto this field, onto this nature leaving only strips of land. All of this is full of meaning; it is the last sign of the outgoing world.

Malevich was not a peasant by origin, his father was an engineer at a factory, however he grew up in a village in the south of the Ukraine, and this greatly influenced him.

COLOR

Malevich had a theory on color, he thought that color depends on where the person lives, if in the city it is the prevalence of black, gray, brownish black, dark blue, in the countryside it is the love of bright colors, colorful shirts, necklaces, painted stoves, shutters, he liked all of this. His descriptions of weddings are wonderful. The bride is like a fragrant flower in full blossom; men in caracul hats and colored trousers with sash; all this was during his childhood.

Irina:”Isn’t it the case nowadays? The city is more monochrome compared to the countryside, isn’t it?”

I.V. : This is not the point; this has found reflection in his art: one sees that his “cubistic” things are more restrained, although there are contrasts of hues there, one also sees his first and second peasant cycles with rich, bright, “sound” color, with color contrasts. All of this means that his concept “works”. This is very meaningful art, it’s not “formalism”, it is rather a philosophy of life embedded into paints, lines, and plots.

Irina: Malevich is perhaps better known to our readers as the creator of the Black Square. Why is it black?

I.V. : I have written a book on that. Black square has a very interesting story behind it. The square was born out of a memory of his work on the opera “Victory over the Sun”. The fact that the black geometric shape is the antithesis of the sun that is radiant and bright and is a symbol of all the good, benevolent, great, aesthetic, is Malevich’s nihilistic gesture.

Irina: What is his attitude to color?

I.V. : He had a wonderful attitude to color. He believed that color is the main quality in painting, that painting is color. In his article of 1915 “From Cubism to Suprematism”, the first article after the “Black Square” he asks: Why did Matisse, Chagal paint faces in a red color?” He reckoned that color, paint is an independent entity, as nature, and it is unknowable. Color cannot be translated into a depiction of nature and it craves for abstraction. Malevich was saying that the paint “rebelled”, “could not come down” and finally it found its form, the abstract form.

He didn’t have a favorite color. He loved “open” colors, although he uses tonal painting in his impressionistic series. Malevich often uses a triad: red, black, white.

There is a series of books published by a French researcher, Michel Pastoreau, about the history of color: of black, of blue, of red colors and so on. He has an interesting idea that in ancient times people first mastered such colors as red, black, and white, and only then, much later, started to turn to the blue color. This is partly due to the technique, with new dyes that were found, but also with the tastes of people. The ancients loved colors that were simple, meaningful for them.

Malevich possesses this ancient, folk backbone, and that is why he loves the open color and he returns to this in his later works.

MULTIPLICITY OF MEANING

There is still a bit of Suprematism shown in Malevich later works: firstly, the global scale, secondly, the geometrization of figures. Figures are “faceless”, they lack individuality, these are characters that are transformed into a sign.

Irina: Why does Malevich paint empty ovals instead of faces?

At a certain moment he likely understood that it was impossible to find such a face, such individuality, which would have given him the right depth and the meaning’s internal dimensions. It is similar to how composers come to know that the very best sound is silence.

“The Square” holds many different meanings, and later paintings carry a similar multiplicity of meanings. It is essential to note that he doesn’t lose one of the very important qualities of Suprematism – its insolvency. It is a sign that does not have one meaning; you can look into it numerous times and continue finding new meanings.”

CHANGEABILITY

Irina: Critic Efros said: “There is no artist by the name of Malevich, however there are several individuals with this last name”. Does this opinion correspond to your understanding of Malevich?

I.V. : The quality of “proteism” [changeability] was completely misunderstood by our critics. I wrote about it, and Anatoly Strigalev published an article on the anti-innovatory bias of Russian art critics. The point is not that the critique was unprofessional, these were all highly educated, talented people, but they were raised up on aesthetic, retrospective and elegant art, which was further cultivated by the group “World of Art » (“Mir Iskusstva”). They all loved the classics and skeptically regarded new art. And there suddenly appeared artists who built their own biographies completely differently, they were “proteists” who were seeking changes all the time.

Efros and other critics could not understand that. For Efros these were some savages, not personalities, not people of culture. He had a very simple explanation: they look at what’s new in the West, and they take everything from there. When Goncharova, recognized as the most avant-garde at the time, at her personal exhibition in 1913 showed different periods of her work: Impressionism, Fauvism and Cubism, everyone was wondering where is she real? “She is a woman and she is impressible, she can’t arrive at anything. “

Efros was an absolute fanatic on wholeness. He compared the art of Aristarkh Lentulov with a woman’s quilt blanket sewn together from pieces.

The avant-garde artists heavily resisted this toxic intonation. On the contrary, they “attacked” those who found “their face”. Rozanova said: How do we finish off with this “despicable skin”, with this « mask, which is inhibiting the artist’s development?” They knew that the best artists of that time, like Somov, Roerich, and Benoit, as soon as they found their unique style, would immediately start to exploit it.

Comments