Jean – Philippe Jaccard, professor, writer, Head of the Department of Russian Literature at the University of Geneva discusses F. Dostoyevsky’s style with Artdecision’s Irina Vernichenko:

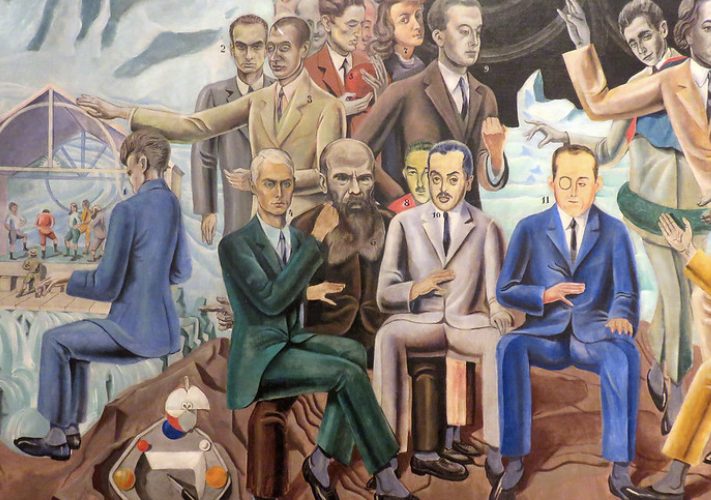

Irina : Max Ernst’s painting “Friends Reunion”, 1922 from the Ludwig museum is a group portrait of artists- surrealist with Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Why do you think Dostoyevsky was portrayed on the painting? To what extent is Dostoyevsky a European writer? Can his novels be linked to expressionism or surrealism?

Jean- Philippe Jaccard: People started to become interested in Dostoyevsky in the end of 19th- beginning of 20th century in Russia, and in the 1920s in the West. André Gide wrote an essay about Dostoyevsky, explaining the concept of the “übermensch” (superhuman). These were questions which came to life with the emergence of fascism and “übermenschen” in the inter-war period.

In the context of the 1930s and the start of the Second World War Albert Camus became interested in the notion of a “Man of the Absurd”. I believe that this is exactly the kind of a person that Dostoyevsky talks about, and that this is not a foreshadowing surrealism but rather existentialism.

This depiction of Dostoyevsky on this canvas can be interpreted differently, only a researched the painting, a historian of surrealism can answer, what lies behind it.

Dostoyevsky is the kind of a writer who appeals to everyone not only to Russians. Although, in the 19th century he seemed to be a nationalist by defending the «Holy Russia» from all opposers, Dostoyevsky has proven to be more universal than both he himself, and the literary audience thought.

The interest in Dostoyevsky was also linked to the “literature de l’inquiétude”, characterised by anxiety and a sense of fearfulness, which emerged as a Post- Avant-Garde movement in the 1930s right before the Second World War.

IV: Are Dostoyevsky’s novels part of the “literature de l’inquiétude”?

J-PJ: Overall, Dostoyevsky is a person “de l’inquiétude” –doubt is the basis of his literary work. He believes in God, of course, but he is afraid of being wrong. Doubt and hesitation are at the core of Dostoyevsky’s most important questions regarding the world. These are the questions which are repeated: 20th century’s catastrophes, wars – “How the belief in God can be defended after all this?”

Voltaire also asked this question after the earthquake in Lisbon in 1755. These are the questions of the age of enlightenment which are to this day unresolved, in my opinion.

RECOGNITION

The recognition of Dostoyevsky began in Russia in the end of the 19th century when following the “ renaissance “ of religion and following Symbolists the perception of him changed, and critics changed the way they wrote about him.

Previously the Nihilists’ criticisms of 1860s was predominantly accepted: everything was explained if not in the context of the class struggle ( this would come later) but in sociological terms. Did Raskolnikov kill because he was poor and annoyed by his environment (“sreda zaela”)? – that is how he was explained by sociologists.

IV : Does Dostoyevsky resonate with the modern audience?

J-PJ: Dostoyevsky strongly resonates with students.

Firstly, these are timeless questions; psychological, political, spiritual and, hence, they can concern everyone. These problems resonate with young people, because they have questions which they cannot answer, or which they answer falsely, and they themselves understand this.

POLYPHONY

Secondly, his manner of expression, the way he writes, and what Bakhtin described as “polyphony” – the idea that every character has his own consciousness- is very interesting. Characters do not obey the will of the author. L.Tolstoy is “omnipotent” and if his character is negative, this character will act by following the author’s instructions – (this is rough and figurative, but it is what it is). But Dostoevsky “is sitting in a corner” and looking on when this type of character clashes with another character of the same type, and discerning which feelings arise as a result of this clash. He does not involve himself and gives the characters their own free will.

Thus, any reader from any time period is attracted to the novel and he must speak his mind: in Dostoevsky’s novels everyone states: “I think like this, I think like this” and the reader wants to speak, as there is a place for him – this is one of Bakhtin’s most interesting ideas.

IV : How do readers interpret Dostoyevsky’s relationship towards the West?

J-PJ: Dostoyevsky’s type of thinking is rooted in the Middle Ages. An example of this is Myshkin’s speech from the novel “ Idiot”, when he breaks the Chinese vase. Later, Dostoyevsky talks about the Russian Orthodox togetherness and about Western individualism, the idea also shared by Slavophiles.

This is partly true. The Protestant spirit, the relationship towards individuality, so prevalent in Western countries (and to a slightly lesser extent in Catholic countries) is hard to grasp for a Russian.

Another example is the concept of unowned land, “which belongs to none but God”, hence peasants work the land together, communally.

When after the “perestroika” people started talking about land ownership, that it is important to develop capitalism in Russia, a lot of the discussions were around can land belong to an individual person at all.

This divide between Europe and Russia was always there, and from this perspective, Dostoyevsky is a typical orthodox “pochvennik” and this is where most of his xenophobic statements come from, which is quite unpleasant. How can a writer of the highest level talk like this?

HIGHEST LEVEL

IV :« A writer of the highest level », what is your understanding of it?

J-PJ: This is hard to put into words, but I’m just convinced in this after re-reading Dostoyevsky numerous times. I see that he really did not know what he was doing, when he was writing, and this is obvious. This is where there is a huge difference with postmodernism, where everything is meticulously planned out. His inspiration evidently comes from elsewhere. He was never satisfied with his work and once, he wrote to his publisher: “I did not even say a tenth of what I wanted to say”, but it turns out he has such an unbelievably full meaning in his novels.

This shows mastery because it is supported by the novel’s structure. My approach is part of structuralism – I look at how the novel is built and I see that Dostoyevsky did not know where he was going. For instance, he wrote to his publisher after finishing the first part of “The Idiot”: “I’ve got these characters on my hands. I don’t know what will happen with them tomorrow”. He did not know, he just observed.

In his rough drafts, the idiot is a very negative person, it was not the idiot who should have become Myshkin. Alyosha could have been a criminal… There are radical inversions of characters. There exists this range of possible actions for characters – Dostoevsky implied this in every novel.

Therefore Myshkin is not 100 percent Christ-like, because he is human, his naïveté does not save him.

There is also the question strictly about his writing: Dostoyevsky writes, hurries up, sends one part to his publisher, does not know how to proceed, and later on you read that in 50 pages he describes something completely different – the Ivolgyns and others, and we lose Myshkin.

It seems that everything goes like that. But when one does a detailed analysis of the novel, one sees that nothing is lost from the novel’s structure, the novel is perfectly symmetric, in terms of characters and actions like a metronome. As it turns out, it is a flawless work of art that is finished, but Dostoyevsky thinks it is not.

It is a mark of genius to write a work that is higher than himself.

IV : It is known that Dostoyevsky read newspapers every day and that he based his novels on real life events.

J-PJ: He was a person who was interested in present day issues, which is seen from his diary and from work for journals, such as “Epoch” and “Time”. This was a time of great reforms, the emergence of court witnesses. He read articles about court procedures, wrote articles for magazines. He started to theorize how a human being could get to that point.

Dostoyevsky always chooses traumatic situations hence many people do not like him – everyone is anxious, crazy, etc., far from how it is in real life. He chooses the moment when a person is still undecided whether to kill or not, to be a saint or not to be one.

These are the questions which consume him. If he takes an event from real life, he later structures a novel around it – i.e. through fiction he can get a better grasp on how it works, he looks at how people react to one another and he looks at how a thought pops into Raskolnikov’s mind, where it comes from.

IV :Was a theme of entertainment contradictory to Dostoevsky?

J-PJ: There were no contradictions. This was expected by the public.

There is a trend – the mass audience turned to TV shows. Then, in the 19th century there were feuilletons, serial novels. The most popular later became A.Dumas. Dostoyevsky’s genius lies in the fact that he takes this A. Dumas’ structure when he writes, but the contents are completely different. This is brilliant because the important, essential, timeless questions are in a novel which formally looks like an adventure novel.

Dostoevsky did not exactly know what he was writing. Hence, interpretations of his work were not fully correct. For instance, when he wrote his first literary work “The Poor People”, he was 25. He was young, proud and after Belinskiy praised him he gained a lot of popularity. People and he himself thought that he was inspired by the spirit of the time writing about poor people, about their misfortunes – these were social works.

Later he wrote a romantic fictional novel “The Double” à la Hoffman, which was different. He was young, absorbed everything, read a lot and tried to imitate former literary greats, including Gogol, Balzac. His romantic translation of Balzac was dreadful.

He himself does not understand that he is writing differently already in the 1840s. Therefore, “The Double” is an amazing work which Belinskiy did not approve of and consequently, Dostoyevsky’s aura faded and his critics were saying that he was not a “Natural School” progressive writer. This always happened to him.

IV : And what is the most interesting of his works to you?

J-PJ: His works as one whole, his “Pentateuch”, his 5 major novels, which we can absolutely reasonably judge as one literary work, and the different chapters of the work are interlinked : from “Crime and Punishment”, “The Idiot”, “Demons”, “Teenager” to “The Brothers Karamazov”.

What happened prior to that? The 1840s were when the “natural school”, Belinskiy, socialism, adventure novels, Balzac, romantism all emerged.

Later, he was sentenced to 10 years of prison camp and was absent for 10 years. After his return “The Humiliated and the Insulted” was published, which is considered as a transitionary novel. In my opinion, it is a brilliant and underrated novel.

From the perspective of his literary career, the first crucial moment is when he re-emerged in St. Petersburg once again. In the beginning of the 1860s he participated in journalistic life, in various debates and reforms.

And secondly, he fights in his literary works against Chernyshevskiy’s ideas, which begins with “The Humiliated and the Insulted” and above all, with the powerful work “Notes from the Underground”. There is also the problem of freedom, which is at the center of “Notes from the Dead House” – this is all during the start of the 1860s, and it marks his latest steps, where his biggest question is the question of freedom: “If a person lives in a golden castle (Crystal Palace) without the possibility of leaving – is this freedom?” (10th chapter of “Notes from the Underground”) – this was about the utopian socialism which he previously believed in.

IV : And should a writer be a publicist and an activist?

J-PJ: No, he can, but he does not have to be both. Very often becoming a publicist harms a writer. For example a good writer like Valentin Rasputin became a publicist and later disappeared. For Dostoyevsky this did not work.

IV : Is the connection between a publicist and a writer stronger in Russia than in the Western literature?

J-PJ: I think so. I think that Belinskiy is “guilty” of this. First, he is guilty in a positive sense – he directly said that a critic played a large role. In Tsarist Russia you cannot start talking about politics, but opinions have to be stated – writers can state any of them ( this was the “Natural School“).

This is where the responsibility of the writer as a citizen comes from.

Belinskiy said that a critic helps a writer by pointing him towards what he should be writing about and then educating the public.

This is a knot, which ties during the 19th century, and which was harmful in reality, as it was decided that aestheticism à la Pushkin was not interesting : “Enough, it was during the golden century”. Now, the citizen- poet Nekrasov, “populist”writers such as Uspenskiy talk only about the sufferings of people. In Russia, in the end of 19th century poetry was practically no longer written, even though Russia is a country of poetry. Fet, Tyutchev and that was it, it was not until the end of the 19th century that a rebirth of poetry took place, in particular with the Symbolists movement.

Belinskiy probably slowed down some processes.

And when Soviet writers in the 1930s started to say the same thing but in a more vulgar way, this was also detrimental towards literature and art. Writers were jailed, died – this happened to the best writers.

IMAGES OF WOMEN

IV: Dostoyevsky overshadows other writers and clearly has a link to modernity. Out of all his portrayals of women, which image is the most modern?

J-PJ: Unlike Turgenev’s women, which are stuck in their own time, Dostoyevsky’s women are not. Characters such as Nastasya Fillipovna are universal. Nastasya Fillipovna and Aglaia have distinct personalities.

They do not do anything, they do not even eat, they sometimes drink tea, but nothing more – they do not lead a material life, they socialise. This is like a theatre.

Dostoevsky sometimes leaves “he said” so, for 10 pages, but we know who is talking – because it’s the same as in theatre. Thus, this is what interests him: the social interactions between characters and the clash of personalities.

The portrayals of women are universal, but of course the city, the entourage of St. Petersburg plays an important role. The characters exist in our world today, it is possible to meet some Nastasya Filippovna nowadays. Maybe you won’t see Nastasya Fillipovna every day, because she is so bright.

IV : Is this not the Russian type?

J-PJ: To a certain extent not. They are exaggerated. Dostoyevsky wants this type of spontaneous personality, which exists throughout the whole world to be finalized to the extreme, in order to analyze the limits of this personality, and to what it can lead.

IV: How did your interest in Dostoevsky emerge?

J-PJ: I organized the 2004 conference on Dostoyevsky in Geneva and always avidly read his works. As a literary critic I have to understand why I like it so much. I specialize in 20th century avant-garde but always read Dostoyevsky.

HEAVYWEIGHT STYLE

IV : What kind of stylistics Dostoyevsky had?

J-PJ: It is his stylistics. It reflects the complexity of his thought process. All these difficult, long sentences. In the translations his stylistics were flattened, repetitions were removed, one sentence turned into three.

I was very surprised by his “heavyweight” style – it is not clumsiness, he does not write poorly, but it is his distinctive style. These repeats are all meaningful. The complex structure is also meaningful.

I had to understand why this is so brilliant? This is my work – I analyze the text and preferably the texts of those authors who I am more fond of.

This is the mystery of literary taste, taste of works of art.

NEW TYPE OF NOVEL

Dostoyevsky is one of the biggest European writers of his time, 19th century and in general. He revolutionized the art of a novel, a new type of novel emerged – in Russia.

A new type of novel is what I said about the genres. Which genre does “Crime and Punishment” belong to? Is it a novel? A feuilleton? An adventure novel? A psychological novel? There is no definite answer.

It seems to me that the genres were defined in Europe and suddenly Dostoevsky offered what Bakhtin called a “polyphonic novel”. It is a completely different genre. And the writers of that time turned their attention to it, starting with Andre Gide.

And thematically, philosophical questions on causeless action, or inexcusable crime were asked.

Dostoyevsky influenced European writers as well, not only Russian writers.