While we are staying at home during this critical time, I hope you enjoy reading this review of the retrospective of Olivier Mosset’s work at MAMCO, Geneva, as well as his work shown concurrently at Gagosian, Geneva, and that once we are free to go and see art again, you will be inspired to see these shows in person.

In order to understand Olivier Mosset’s work it is important to mentally travel back to the heady 1960’s, when there was a radical re-thinking of societal norms in the art world and beyond. Swiss-born Mosset moved to Paris in 1964, where he immersed himself in the art scene. Mosset worked for Jean Tinguely as an assistant, and mixed with many of the most influential artists from the time, including Niki de Saint Phalle and Andy Warhol.

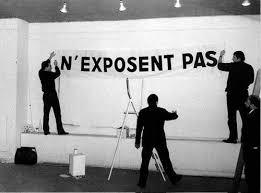

In 1967, Mosset and his friends Daniel Buren, Michel Parmentier, and Niele Toroni began a series of planned disruptions within the Parisian art world. These were designed to overturn the established ideas of artistic creation and ownership and their attention-grabbing art-world pranks became the talk of Paris. For example, in 1967, at the opening of the Salon de la Jeune Peinture, instead of presenting finished pieces and maintaining the mystery of creation, they live-painted their works, showing that anyone could make a painting. They then removed their paintings and replaced them with a banner reading “BUREN, MOSSET, PARMENTIER, TORONI N’EXPOSENT PAS” (DO NOT EXHIBIT).

And this attitude is the foundation of Mosset’s work – a questioning of what art is, with an aim of contributing to a radical change in society. Questions such as: who owns art, why is some art worth more than other pieces, and who determines the value of art, are at the core of Mosset’s work. The paintings we see today are part of a movement whose goal was to break with prevailing artistic traditions, if not to change the world. While viewing his work at MAMCO, as well as the pieces at Gagosian, this is the lens through which his work can be seen.

The retrospective at MAMCO is an extensive and varied display of Mosset’s work from his earliest creations through to contemporary pieces. The exhibit meanders through Mosset’s main themes including the circle pieces, striped paintings, monumental “non-paintings”, and red pieces, among others, following a chronological order within the themes.

Starting with the circle paintings, these achieved critical success in the early 1970’s and established Mosset as a known conceptual artist. There is an entire room full of these paintings at MAMCO. They are all the same; the canvases are 1 meter x 1 meter square, painted white, with a black 3.25 cm thick circle in the center. Between 1966 and 1974, Mosset painted about 150-200 of these, all untitled and unsigned. Along the same lines as Warhol was doing at the time with his Campbell soup can pieces, they question the concepts of authorship, authenticity and value.

However, while making a statement against the commoditisation of art, Mosset actually gained commercial success with these paintings and the motif threatened to become his trademark. As Mosset said, “I was doing the circle paintings and I thought that I was going to do them for the rest of my life. And maybe the world was going to change or something like that. Of course the world hasn’t changed and at one point I had enough of these and I went and I thought that this is silly and I went and I did something else.” He turned away from the circle to pursue other themes.

Another interesting room is the collaborative project from 2001 of Mosset’s work with well-known Swiss artists Sylvie Fleury and John Armleder. This combination is a tradition going back to when MAMCO first opened its doors in 1994, when it hosted an exhibition in three rooms of these artists. This idea was repeated several times and one of these reiterations is at MAMCO now. It is an interesting juxtaposition of Mosset’s striped paintings, with Armleder’s pile of crushed, jumbled industrial rubbish, and Fleury’s Mondrian boots scattered on the floor. Taken together, it is a layered mixture that questions ideas of the value of art, while critiquing industrialisation and consumerism.

An eye-catching part of the show is the red-themed room with large shaped-canvases as well as huge, monumental pieces. The burst of red brings a joyous quality to the space, and one can lose oneself in the depth and intensity of color. In an interview in 2015 in Tucson, Arizona, Mosset stated: “You can sit in front of a Rothko and look at what’s happening, and with my paintings you can do the same.” Shades and nuances of color appear and disappear as one gazes into the pigment, tricking the eyes and the mind into seeing shades that are not there. The use of color is unapologetic, and these are paintings just because they are.

In addition, there are rooms full of huge colourfully striped pieces which both delight and tease the viewer in terms of color combinations, and scale. The size of some canvases borders on the absurd, and as Jean Baudrillard, the French philosopher and cultural theorist stated, they are “paintings that are not paintings.” Instead they are “An instrument of vengeance that ridicules all the ambient pathos of signs and messages.” While most are untitled, one from 1989 is titled “Patricia’s pillow (second version)”, elevating an everyday household item to the subject for a monumental painting. Another painting title is “Second Harley”, honestly stating what the sale of the painting will buy for the motorcycle-obsessed Mosset.

Following on this is the painting titled “Babyliss” from 1991. Babyliss is, of course, the French-based firm that sells curling irons to make hair wavy. T his painting is tucked into a space specifically designed for it and the canvas undulates like a vast slab of curled tresses. Again, elevating a household brand to the status of fine art, Mosset is playing with ideas of the definition of art, and what subject matter is appropriate or not, as well as who decides on these issues.

At Gagosian, Geneva, the paintings shown are an extension to the MAMCO show. As Swiss artist John Armleder once said of Mosset, “He is a radical, classic artist who creates a new world.” The four paintings at Gagosian create an immersive, contemplative world based on the classic diamond shape within the white-walled space. Each piece is “Untitled” and black, however, in a slightly subversive way, Mosset has added hues of yellow or red or green or blue to each canvas, and if you look very closely, what first appears as black reveals a greater nuance.

What one initially sees with these so-called black paintings is not what is actually there. This is exactly what Mosset wants to communicate, that he has made multiple paintings that may look the same, but they are slightly different, slightly individual. Similar to the circle paintings, these multiples are not made by machine, but have a human touch. This makes them interesting, especially as a group where one can compare the shades and hues with each other.

Mosset now lives and works in Arizona where he has plenty of space to make his pieces, and his huge paintings dry quickly in the desert air. He can also ride his Harley without a helmet, again breaking with conventions, which suits his style. In an interview with Mosset in 2015, he said, “Now I am more relaxed because I know that they (the paintings) are not going to change the world, to begin with, but it is a little more selfish, a little more personal or something like that and then, well, people can deal with it or not.” This is how Mosset has been creating art for his entire career, doing what he likes to do, making what he likes to make, whether anyone else approves or not. And that is still very radical.

Written by: Kristen Knupp Published: April 16, 2020