The Gurlitt art trove currently exhibited at the Kunstmuseum Bern shows the “degenerate” art portion of the collection, that is, some of the 20,000 pieces of art confiscated from German museums during World War II by the National Socialists. The rest of the trove is being shown simultaneously in Bonn and focuses on art taken from individuals. The two exhibitions will swap places in March 2018.

Much has been written about Cornelius Gurlitt and his father, the art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt since the art trove was discovered in 2012 in Cornelius’s Munich apartment and Saltzburg house. During the war, Hildebrand Gurlitt was one of four art dealers who were responsible for marketing “degenerate” art confiscated from German museums. He was also involved in an official capacity with acquiring art for Hitler’s Fuhrermuseum in Linz.

As a result of this activity, Hildebrand Gurlitt had 22 crates of artwork in his possession at the end of the war. When questioned by the Allies about the art, Gurlitt managed, through telling half-truths and lies (for example that all the records of his art dealer business had burned in the Dresden fire) to escape punishment. Subsequently, the artwork was returned to him. In addition to this known art collection, Gurlitt had many pieces hidden in Paris and in Germany that he and his family quietly retrieved in the years after the war. These form the art trove that Cornelius and his sister inherited.

This art collection was apparently a heavy moral burden to bear. As his sister wrote to Cornelius in 1964: “And what became of his (Hildebrand’s) collection? Do you ever enjoy what you have of it in Salzburg? For us, I sometimes think, his most personal and most valuable legacy has turned into the darkest burden. I tremble with fear every time I even think of it. What we have is locked away in the graphics cabinet or kept behind pinned-up curtains – no one sees it, no one enjoys it. When we think of it we think of tax inspections, war and its dangers, family rows – not as a living memento and symbol of Daddy’s life’s work, or how proud he was of it, and how much more it meant to him than its monetary value. That has all gone to the grave with him, so to speak. It had to be that way, it couldn’t be altered.”(p 44)

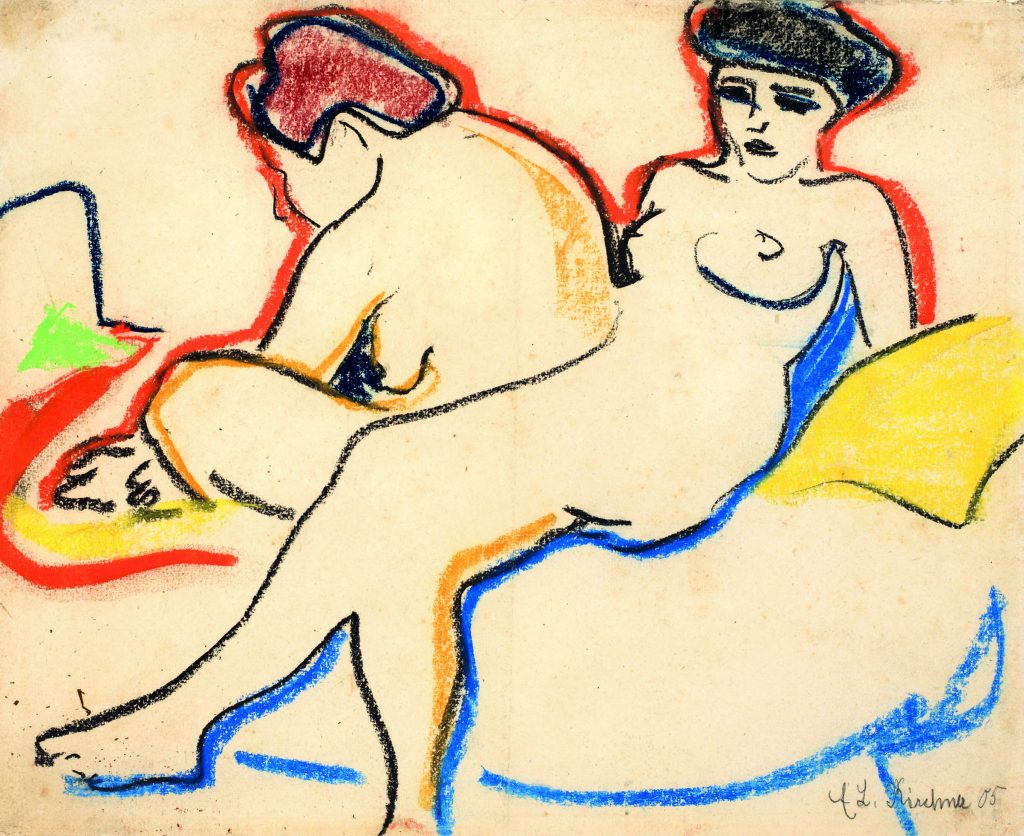

The catalogue for the exhibition, Gurlitt: Status Report, focuses on the extensive provenance research that has taken place since the art trove was discovered in 2012. A team of investigators have examined the ownership history of every piece and have scoured all records and correspondence to discover where the pieces came from, and if they were legitimately obtained or not. Five works have so far been returned to the heirs of their former owners including Henri Matisse’s Seated Woman, Max Liebermann’s Riders on the Beach, Adolf von Menzel’s Interior of a Gothic Church and Camille Pissarro’s The Seine and the Louvre. Searches for the rightful heirs of the remaining pieces continues.

As the Directors’ Forward in the catalogue states, “Provenance research which represents a substantial basis for our exhibitions is a cumbersome business of often tedious and minutely detailed research.” The focus of the exhibition is a “fact-oriented status report” which the Directors feel is the “appropriate strategy for an objective investigation of this obviously explosive topic”. (p 11)

This research process is on-going and will continue in Bern, and with extensive resources now devoted to provenance reviews in many other museums as well. As stated in the catalogue “Cornelius Gurlitt has involuntarily propelled the debate regarding art looted by the Nazis forward to a greater extent than any political or cultural initiative could ever have achieved.” (p 75)

The increasing importance of provenance research of museum collections is further emphasised by an recent announcement made by the French President, Emmanuel Macron, on a trip to Burkino Faso. During his speech, Macron stated that “In the next five years, I want the conditions to be met for the temporary or permanent restitution of African heritage to Africa.” This appears to be a shift in attitudes on restitution of art from Africa that is currently held in French state-owned museums.

What is the future of art collections around the world which have been acquired over long periods of time and in many different ways? Will museums begin or continue in a more thorough manner and with more dedicated resources, to examine the provenances of the artwork in their collections? In Switzerland and Germany, thanks at least in part to the uncovering of the Gurlitt art trove, the process has gained considerable momentum.

Kristen Knupp

Comments